VENEZUELA'S REAL OIL CRISIS. Why the World’s Largest Reserves Became an Economic Dead End

- lhpgop

- Dec 22, 2025

- 6 min read

Executive Summary

Venezuela’s oil crisis is not the result of a single policy failure or sanctions alone. It is the outcome of geology, economics, and governance colliding. Venezuela possesses enormous oil resources, but they are overwhelmingly extra-heavy, capital-intensive, and unforgiving of mismanagement. When the country nationalized its oil sector and expelled international oil companies (IOCs), it removed the only actors capable of operating such assets sustainably.

This report explains:

How oil companies demonstrate value to investors

Where Venezuelan oil fits within a global IOC portfolio

Why oil quality matters more than sheer quantity

What nationalization cost foreign firms—and Venezuela itself

Why Donald Trump frames the issue as restitution, not profit

Why even a post-socialist Venezuela faces a long, painful recovery

I. How Oil Companies Show Value to Investors

Oil companies are not valued on ideology or reserve bragging rights. They are valued on their ability to convert proven, economically recoverable reserves into reliable free cash flow over time.

Core Valuation Drivers

1. Quality-Adjusted Proven Reserves (1P)

Only reserves with ~90% extraction certainty count fully

Heavily discounted for poor quality, high cost, or political risk

2. Free Cash Flow (FCF)

Cash left after operating costs and reinvestment

Determines dividends, buybacks, and debt reduction

3. Capital Discipline & ROIC

How efficiently capital is deployed

High reinvestment burdens reduce valuation multiples

4. Jurisdictional Stability

Contract sanctity

Rule of law

Currency convertibility

5. Decline Profile

Long-life, slow-decline assets are prized

Assets requiring constant reinvestment are penalized

Bottom line:

Investors reward predictable, low-risk cash generation, not raw barrel counts.

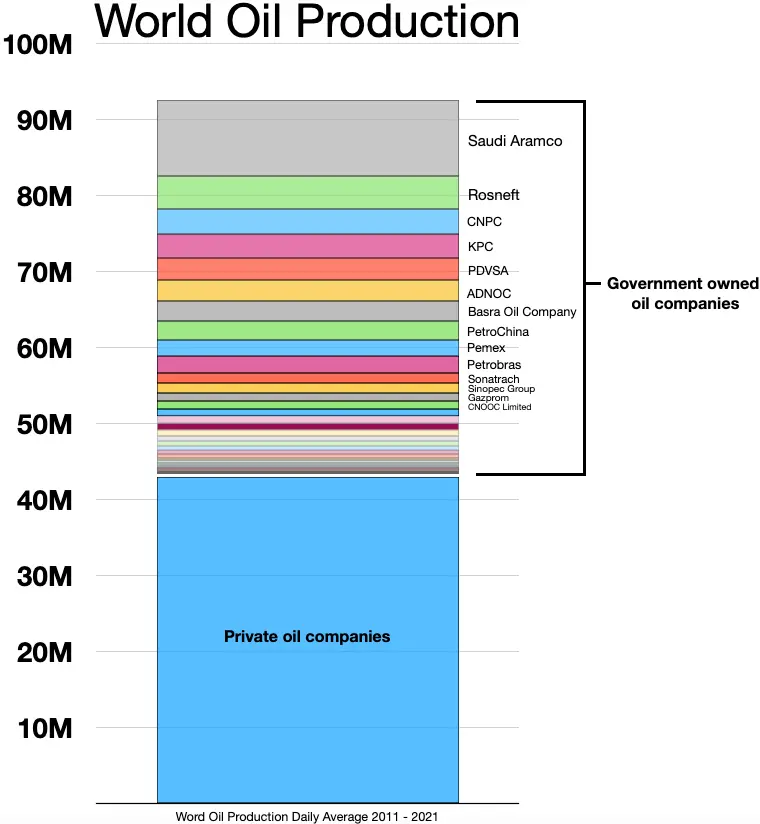

II. Where Venezuelan Oil Sits in an IOC Supply Chain

In an international oil company portfolio, Venezuelan oil historically functioned as a strategic but marginal component, not a core profit driver.

Venezuelan Crude Characteristics

API gravity: 8–16° (extra-heavy)

High sulfur and metals

Requires:

Diluent blending

Upgrader facilities

Specialized refining

Portfolio Role

Not a loss leader, but not a top performer

Margins thinner than:

U.S. shale (good acreage)

Offshore Brazil

Guyana light crude

Economically viable only at scale and with flawless execution

For IOCs, Venezuelan barrels were:

Tolerable when managed professionally

Replaceable when risk escalated

Markets already priced them at a discount.

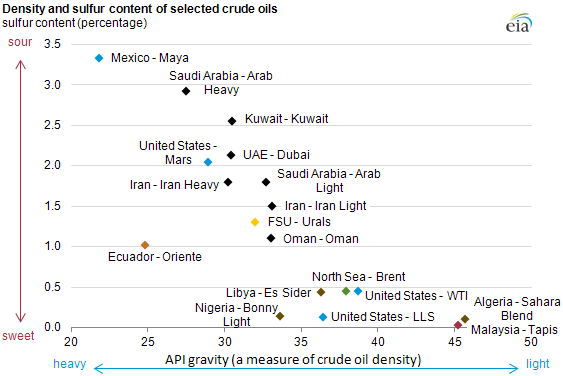

III. Oil Grades: Quality Over Quantity

Simplified Oil Quality Spectrum

Grade | API Gravity | Typical Economics |

Light sweet | 35–45° | High margin, flexible |

Medium | 25–34° | Moderate margin |

Heavy | 10–24° | Low margin |

Extra-heavy | <10–16° | Capital intensive, fragile |

Venezuela’s reserves are concentrated at the bottom of this spectrum.

Operational Reconciliation Required

To integrate Venezuelan crude, an IOC must:

Blend with imported diluents

Maintain complex upgrader systems

Schedule specialized refinery runs

Absorb higher downtime and capex

This makes Venezuelan oil structurally inferior to lighter alternatives.

IV. Nationalization: What It Cost International Oil Companies

When Hugo Chávez nationalized oil assets (2006–2007):

Direct Corporate Impact

Seizure of equity stakes

Loss of sunk capital

Forced contract renegotiations

Estimated losses (conservative):

ExxonMobil: ~$2–3B

ConocoPhillips: ~$4–5B

Chevron: ~$1–2B

European majors: ~$5–10B combined

Arbitration awards were issued—but largely unpaid.

Market Reality

Venezuela exposure was a small share of IOC portfolios

Losses were mostly non-cash write-downs

Stocks tracked oil prices and capital discipline—not Venezuela

Big Oil survived. Venezuela did not.

V. What Nationalization Did to Venezuela’s Economy

Before nationalization:

~3.2 million barrels/day production

Steady foreign capital and expertise

After politicization of PDVSA:

Engineers purged

Capex diverted to social spending

Maintenance deferred

Corruption institutionalized

Results:

Production collapsed below 1 million bpd

Oil revenue imploded

Imports collapsed

Currency hyperinflation

Mass emigration

Economy contracted by over 70% at its worst

Oil did not fund socialism—socialism consumed oil.

VI. Why President Trump Wants the Oil Fields Returned

When Donald Trump speaks of “getting the oil fields back,” the motive is not commercial extraction.

Strategic Rationale

Property Rights Enforcement

Prevents expropriation from becoming permanent

Deterrence

Signals to other regimes that theft has consequences

Regime Delegitimization

Frames PDVSA control as stolen, not sovereign

Avoiding the Cuba Trap

Refusing to let time legitimize nationalization

The oil itself is low-margin.The precedent is priceless.

VII. The Cuba Parallel (Briefly Introduced)

After Fidel Castro nationalized U.S. assets in 1960:

Property claims froze

Sanctions hardened the regime

Expropriation became permanent through delay

Trump’s Venezuela posture reflects the lesson:

Unanswered nationalization becomes irreversible.

(A full treatment of Cuban nationalization and its long-term consequences is reserved for the Appendix.)

VIII. The Post-Regime Reality: Why Oil Won’t Save Venezuela Quickly

Even under a new government:

Oil quality remains poor

Infrastructure repair costs exceed $100–150B

Security and political risk persist

Capital will be slow, conditional, and expensive

Oil revenue will go first to:

Repairs

Debt

Imports

Social stabilization

Not prosperity.

Final Conclusion

Venezuela’s oil crisis is not a mystery and not a conspiracy. It is the predictable result of marrying the world’s most difficult oil to a political system that destroyed capital, expertise, and trust. International oil companies lost assets—but Venezuela lost its economic future. Even after socialism, recovery will be slow, fragile, and constrained by geology and history. Oil will help eventually, but it will not redeem Venezuela quickly.

Appendix A: Cuba and the Permanent Cost of Nationalization

How Delay Turned Expropriation into a 60-Year Economic Dead End

4

A. The Cuban Nationalization Timeline (Condensed)

1959

Fidel Castro assumes power.

1960

Nationalization of:

U.S.-owned oil refineries (Esso, Texaco, Shell)

Sugar plantations

Utilities and banks

No compensation provided.

1961

Bay of Pigs invasion fails under John F. Kennedy.

Castro regime survives → expropriation normalized in practice.

1962–1964

U.S. embargo imposed.

Property claims frozen, unresolved.

Cuba aligns with the Soviet Union.

B. The Legal Reality: Property Lost, Claims Preserved—but Unenforced

Over 5,900 certified U.S. property claims (FCSC)

Estimated value at time of seizure: ~$1.9 billion (1960 USD)

Adjusted value today: $8–10+ billion

Zero restitution paid

Over time:

Claims became diplomatic abstractions

Assets decayed or were repurposed

Expropriation hardened into “history”

C. Economic Consequences for Cuba

Despite:

Soviet subsidies

Preferential trade

Strategic importance

Cuba experienced:

Chronic underinvestment

Infrastructure decay

Low productivity

Persistent poverty

Dependency rather than development

After the Soviet collapse:

“Special Period” austerity

Near economic collapse

Long-term stagnation

Key lesson:

Nationalization without restitution did not produce sovereignty—it produced dependency.

D. The Strategic Lesson for Venezuela

Cuba taught U.S. policymakers that:

Time legitimizes theft

Sanctions alone do not restore leverage

Unresolved expropriation becomes permanent

Regimes outlast patience

Trump’s Venezuela posture reflects this lesson:

Keep property claims alive

Tie legitimacy to restitution

Refuse to let nationalization “age into sovereignty”

E. Why Venezuela Is Not Yet Cuba—but Could Become One

Cuba | Venezuela |

Expropriation accepted over time | Expropriation still contested |

Claims frozen | Claims actively referenced |

Regime normalized | Regime delegitimized |

Oil marginal | Oil central but degraded |

The window to avoid a Cuba-style permanent loss still exists for Venezuela—but it is closing.

Appendix Conclusion

Cuba demonstrates that nationalization is not a temporary political act but a permanent economic decision. Once expropriation survives its first challenge, it becomes normalized, and recovery becomes generational rather than immediate. Venezuela’s tragedy is not that it followed Cuba ideologically—but that it followed it structurally. Whether it escapes the same long-term fate depends on whether property rights are restored before history hardens.

Venezuela’s True Oil Crisis

Endnotes & Sources

Endnotes

[1] Oil Company Valuation & Reserves

Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE), Petroleum Resources Management System (PRMS) – definition of proved (1P), probable (2P), possible (3P) reserves.

Damodaran, Aswath. Valuing Natural Resource Companies. NYU Stern School of Business.

BP, Statistical Review of World Energy (multiple editions).

[2] Oil Quality & Economics

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Crude Oil API Gravity and Sulfur Content.

IHS Markit, Heavy Oil and Extra-Heavy Oil Economics.

API (American Petroleum Institute), Crude Oil Quality and Refining Impacts.

[3] Venezuelan Oil Characteristics

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), Assessment of the Orinoco Oil Belt.

EIA, Venezuela Country Analysis Brief.

PDVSA historical technical filings (pre-2007).

[4] Nationalization & Corporate Losses

International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID):

ExxonMobil v. Venezuela

ConocoPhillips v. Venezuela

SEC filings (10-K) from ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, Chevron (2006–2012).

Financial Times, Wall Street Journal reporting on arbitration outcomes.

[5] PDVSA Decline & Economic Impact

OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin (production figures).

IMF, World Economic Outlook (Venezuela GDP contraction).

World Bank, Venezuela Economic Indicators.

Brookings Institution, The Collapse of Venezuela’s Oil Industry.

[6] Rehabilitation Cost Estimates

Baker Hughes / Schlumberger technical assessments (industry commentary).

Atlantic Council, Rebuilding Venezuela’s Oil Sector.

CSIS, Venezuela’s Oil Industry: Prospects and Challenges.

[7] U.S. Policy & Property Rights

U.S. Treasury (OFAC) sanctions documentation.

U.S. State Department statements on expropriation and arbitration.

Public remarks and policy statements by Donald Trump (2017–2020).

[8] Comparative Case: Cuba

U.S. Foreign Claims Settlement Commission (FCSC), Cuban Claims Program.

Department of State, History of U.S.–Cuba Relations.

University of Miami Cuban Heritage Collection.

Comments